LANDSCAPE AT THE KYAGAR

YEAR

LOCATION

STATUS

CATEGORY

TYPE

BUILT UP AREA

SITE AREA

PHOTOGRAPHY

2025

Kyagar, Nubra, Ladakh

Completed

Landscape

Landscape

-

25 acres

Iker Zuniga

The landscapers who didn’t plant

written by Iker Zuniga

A desert is silk. A desert is sand. A desert is rock, and the dry air is the desert too. Mountain peaks of rocks, stones, and boulders—thousands of eons of tons—dry out after being submerged for millions of years under the sea, and then the path to satisfy the thirst starts again. It began with mist, a cloud heavy with water vapor, the rock not being able to absorb it. The waterdrop slides down the rock, around the boulder. And the sun shows through the clouds, evaporates it, and the opportunity is once more lost.

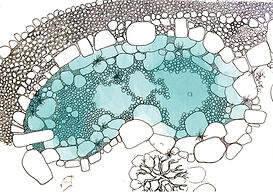

Over time, the same sun that vanishes the waterdrops makes icy water from the mountains begins to melt, and the water flows through the valleys, finding its way down. It moves through Ladakh, to remote places like Nubra Valley, and wherever it reaches, there is a patch of green life surrounded by brown dryness. Now, I am entering the garden designed by Faiza Khan and Suril Patel, founders of the nomadic architecture and design firm Field Architects. The floor is paved with boulder stones of different sizes. Under my feet I can feel their rounded edges. As I walk, I see flowers sprouting from the gaps between the cobblestones. There must be only soil beneath, no cement. Otherwise, they would not grow, and the rocky “path” would be nothing but a dry desert.

The water descends from the mountain and is stored in ponds at different heights across the site; in this way, the amount of water reaching the gardens and the orchard is controlled. Between the ponds runs a little stream, barely carrying water and at points almost indistinguishable from the color of the ground, made visible only by the reflections it casts of the sky. Soon after, I leave this stony area, where the path simplifies. The stones are left behind, and now I walk over the rammed earth they once concealed. The path is elevated, with a limpid thread of water flowing along both sides. Around it, plants of every scent and type seek space near the water. Flowers spill over the path, and makes me pause to notice the tiny details of this miniature landscape.

I look back, and a dog is sitting a few meters away. It is orange, like the dry parts of the landscape. I crouch down to his height and pull my hand away from the plants to bring it closer to his nose. He lifts his tail from the soil and approaches carefully. Smelling the trace of sage on my hand, he lets me stroke his back with the other. After that, he leaves the paved path and disappears into the colorful weeds. I watch it appear and vanish until I finally lose sight of it, then rinse my hand with the glacial water of the stream.

The path is curved and unexpected, shaped by the terrain. Some stretches hide the ground, and others confront you with the forest as if it were a wall. No matter where you look, there is something taller than you. Ahead, to the southeast, is Khardung La: snowcapped mountains rising to more than 6,000 meters. Sharp and jagged peaks, still fervent in their youth. Beside them, the range of Karakorum, the exact point where a mountain chain is born, stretches for more than 500 kilometers and reaches its highest point at 8,611 meters on Mount K2. Northwest the valley where the water comes from, and northeast, a silhouette across the rugged wall is forming because the sun is setting, peeking between the mountain crests and a higher layer of clouds.

Attention feels scattered; all senses receive information at once. I smell wild hervs, I see a snowy peak streaked with white and brown above a tangle of greenish forest, I hear flowing water and birdsongs. The plants are very geometric, distributed in peculiar ways, with a curtain of wheat shielding spiky vegetation behind it. Color and texture dominate—everything else follows. Something makes me think about Pollock, and then I think about the architects again.

I wonder how long it has been since I entered the land, and how much longer until I reach the river. The dog emerges from the bushes and starts walking towards me. Every few meters he stops, checking that I follow. Soon he crosses a stone gate, and beyond it, the river flows with immeasurable force. Part of that force is fed by the small stream— the same one that nourishes these plants, quenches the dog’s thirst, and washed my hands. The sky is red, and so is the water. A few days later, I meet Faiza and Suril on the land at dawn. As we walk, they tell me this landscape will be a desert two months from now. And in six, it will bloom again. “How did you choose all these plants? How did you decide the colors and textures?” I ask them. “We did not select the plants. In fact, no one did,” they reply. “We studied and prepared the land, shaped the paths, distributed the water—so that nature could do its work. When we arrived here, the place asked nothing more of us. For us, the greatest compliment is when what we design blends into its surroundings. When it feels as though it has been here for thousands of years, as if the place itself designed it.” I want a portraits of them and ask them to step off the paved path, outside their design. We take the chance to pick some sour fruits from a sea buckthorn that no one planted, and in this way we say goodbye to the forest before it disappears.